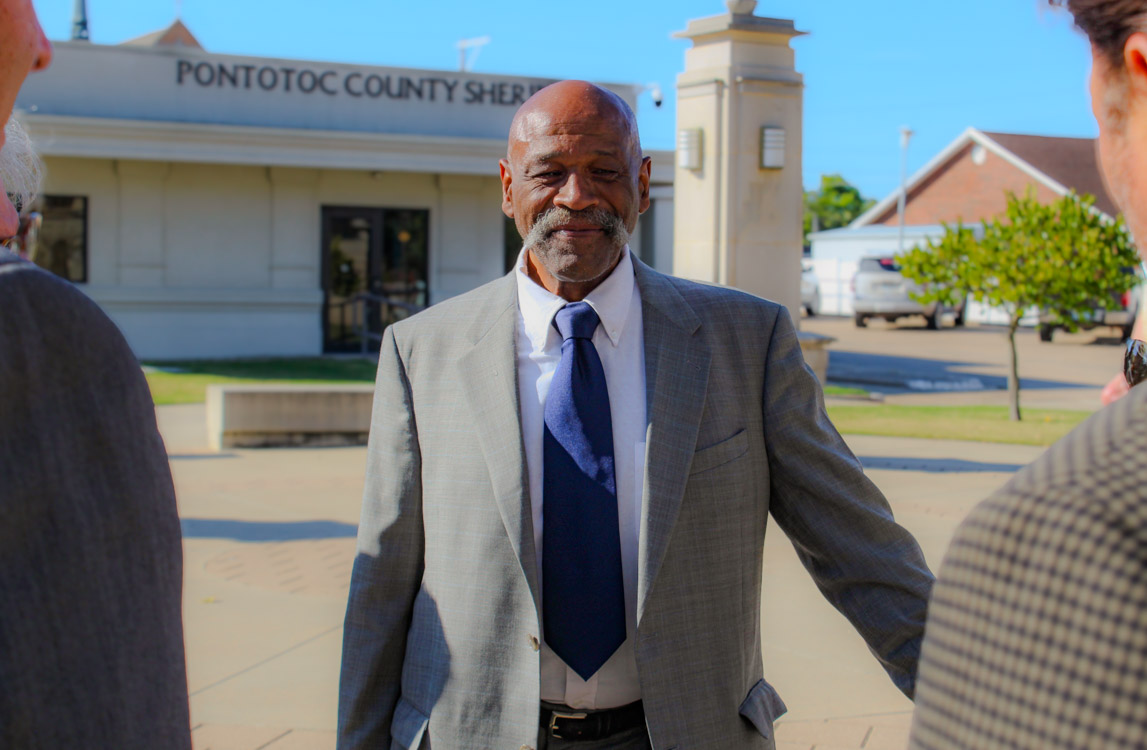

Barry Scheck (left), co-founder of the national Innocence Project, speaks with Norwood.Law client Perry James Lott in Ada, Oklahoma, after Lott’s 35-year conviction for rape was vacated by a judge on Oct. 10, 2023.

By G.W. Schulz

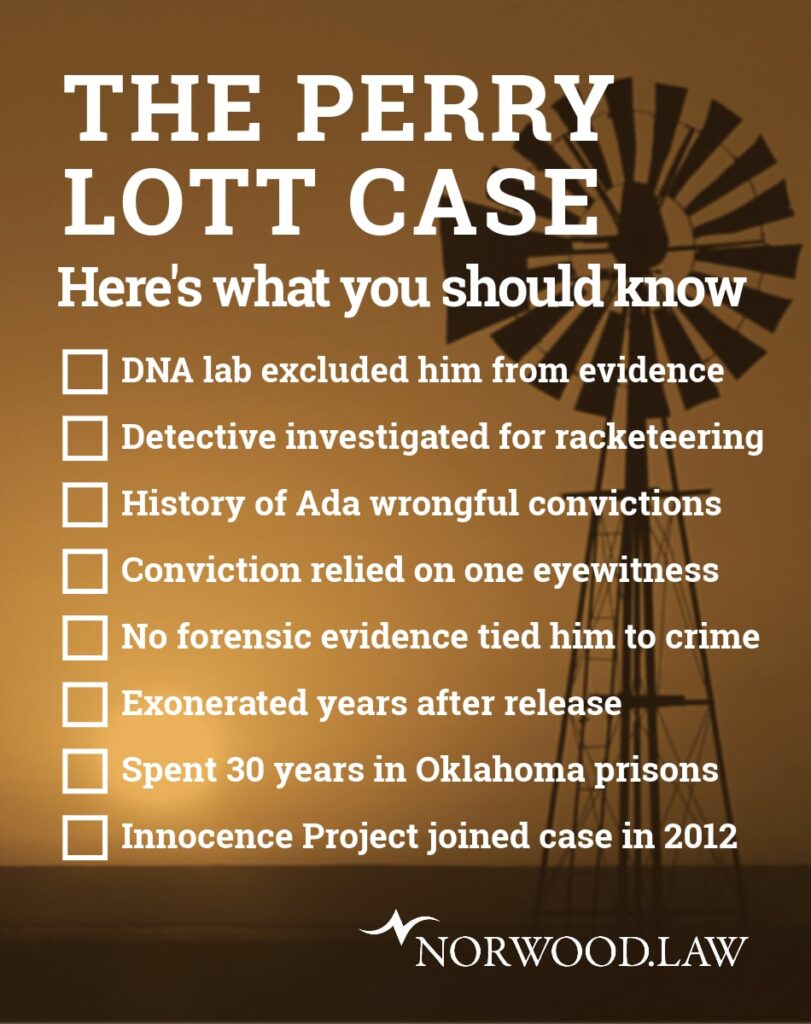

An Oklahoma judge has overturned the rape conviction of a man who served 30 years in prison for rape after a DNA analysis excluded Norwood.Law client Perry James Lott from biological evidence collected in the case. The turn of events occurred after a new district attorney took office in early 2023 and conducted an in-depth review of Lott’s case.

Pontotoc County District Attorney Erik Johnson then appeared at an Oct. 10, 2023, hearing with Norwood.Law and the national nonprofit Innocence Project to request that Lott’s 1988 conviction be vacated and case dismissed. That means Lott is no longer a convicted sex offender in the eyes of Oklahoma law, cannot be pursued again for the crime, and is exonerated of the offense. Johnson said at the hearing that as district attorney, he was as much responsible for protecting crime victims as he was determining whether evidence favored a defendant.

It’s been a long wait for Lott to arrive at this moment. A forensic scientist wrote in a 2017 affidavit that Lott’s DNA was not present in a rape kit collected following a 1987 sexual assault in Ada, Oklahoma. A relatively small, rural community, Ada today has a population of about 16,500 people. Pontotoc County District Judge Steven Kessinger agreed at the Oct. 10 hearing to vacate the conviction and dismiss the case six years after the DNA affidavit was signed.

As a result of the ruling, Lott becomes the sixth-known person to be exonerated after being sent to prison by Bill Peterson, the long-serving and controversial former district attorney for Pontotoc County, the seat now held by Erik Johnson.

Peterson retired in 2007 after nearly 30 years as the top cop of Pontotoc County. During that time, his record of problematic prosecutions drew national attention to Ada in the form of books, news stories, and podcast episodes. The detailed coverage includes a best-selling 2006 book by megastar author John Grisham called “The Innocent Man,” which became a popular 2018 series on Netflix. It is the only nonfiction book ever published by Grisham out of dozens. Bill Peterson attempted to sue Grisham over the book but was not successful.

BREAKING: Perry Lott was just exonerated by DNA after 35 years of wrongful conviction in Oklahoma. “I have never lost hope that this day would come. I can finally shut this door and move on with my life.”https://t.co/IOkjN6zFNi

— Innocence Project (@innocence) October 10, 2023

In the case of Perry Lott, the DNA results enabled him to go free five years ago in 2018. But he wasn’t exonerated at that time. Lott instead had to accept a plea deal and agree to special conditions for release that were imposed on him by another previous district attorney for Pontotoc County, Paul Smith. He has since left office.

“[Lott] has been walking around a convicted rapist for five years on probation,” Joseph Norwood said after the Oct. 10 hearing. “That puts a substantial burden on a person. If you’re applying for a job, you have to tell that prospective employer that you’re a convicted rapist. If you’re applying for housing, you have to tell the housing entity that you’re a convicted felon.”

Without his conviction being vacated, Lott would forever be considered a convicted sex offender in the eyes of the law no matter what DNA testing or any other evidence showed. But District Attorney Smith’s departure from the seat created the possibility that someone new would arrive with a different view of the case. Keep reading below to learn more about Perry Lott’s journey to freedom and Norwood.Law’s efforts to help exonerate him once and for all.

Don’t wait to act if you’ve been accused of a crime. You’ll need passionate advocates to tell your side of the story. And it’s not only criminal law we practice. If you find yourself caught in the web of a family, personal-injury, or business-law dispute, Norwood.Law will represent your interests with the same skill and commitment that we’ve delivered to Perry Lott. We also handle wills, trusts, and estates. When it’s time for you to reach out for help, call Norwood.Law for a consultation at 918-582-6464.

In the meantime, Lott still struggles to rebuild his life after leaving prison. Efforts to secure compensation for the 30 years Lott spent locked up will take a considerable amount of time. For now, a GoFundMe page has been set up to help Lott with medical costs.

New research on eyewitnesses

Perry Lott has maintained his innocence since first being questioned by police about a rape over 35 years ago. Now, in 2023, there was finally agreement on all sides – from the prosecutor to the defense attorneys to the judge – that Lott’s conviction for the crime should be vacated and his case dismissed.

A determining factor was DNA technology, which wasn’t yet available in the 1980s when Lott was first sent to prison. In fact, the DNA results were returned in 2014 showing that male genetic material contained in the rape kit did not belong to Lott. It took four more years before Lott was able to reach a compromise in the form of a “sentence modification” that allowed for his release but not his exoneration. It took another five years before his conviction could be vacated and case dismissed.

“I feel like a newborn baby – being born again,” Lott said outside the courthouse Oct. 10. “I said the same thing five years ago when they released me from prison. And it feels the same way again today – like I’m being born into a whole new life. That’s how it feels.”

Having his conviction vacated and case dismissed would appear to make Lott eligible for entry into the National Registry of Exonerations, which has tracked nearly 3,400 exonerations in the United States since 1989. The registry, which is overseen by the University of California Irvine and other schools, says a person is exonerated when all charges have been dismissed “related to the crime for which the person was originally convicted.” That dismissal “must have occurred after evidence of innocence became available that was not presented at the trial at which the person was convicted.” In Lott’s case, that evidence would be the DNA analysis.

There was no physical evidence used against Lott in the case, and prosecutors at the time in 1988 relied on the memory of the lone eyewitness to gain a conviction following a one-day trial. Extensive research since then into memory, perception, and eyewitness testimony has led criminal-justice reformers to urge greater caution where someone’s testimony against someone else is corroborated by little or no other evidence. Among other things, the witness said that her attacker was clean-shaven. But when police came into contact with Lott just one day after the assault, they noted that he had at least a few days’ growth of mustache.

DNA becomes available

When Lott was first convicted in 1988, DNA forensic science was not yet available to him. Neither was it available to other defendants prosecuted by Bill Peterson, the Pontotoc County district attorney of 30 years who over the course of his career helped push the small town of Ada, Oklahoma, into the national spotlight with questionable convictions. Today, Peterson is retired. But his career as district attorney of Pontotoc County was long and storied. Lott joins at least five other people who were exonerated after being prosecuted by Peterson’s office.

Two of the men were freed by DNA in 1999 after serving 11 years in prison. The DNA evidence revealed that a star witness in the case was the true killer all along. In the second case, one man was found actually innocent of murder by a federal judge in 2019. A state judge vacated the conviction of the second defendant in 2020, but a state appeals court reversed that decision in 2022. At the time the two men in the second case were convicted, no victim’s body had yet been found by authorities, there’s never been DNA available for analysis, and no physical evidence was ever presented against the defendants.

In yet another case from 1982 that was also handled by Peterson’s office, a jury at the time took just 30 minutes to convict Calvin Lee Scott of rape. Police said they had connected Scott to the crime scene through forensic evidence in the form of hair samples. But DNA evidence eventually linked the crime to another perpetrator. Scott was let go after 20 years in prison.

In the case of Norwood.Law client Perry Lott, there were alternate suspects, but the trail to them has been marked by deadends. Three such suspects were excluded by the Innocence Project through DNA testing. The fourth was an Ada sex offender discovered in recent years to be incarcerated. When asked to provide a DNA sample, however, the man refused.

‘I didn’t do it’

The sexual assault of victim Donna Reed occurred past midnight on Nov. 3, 1987. Perry Lott, now 61, was arrested for the crime two days later. Lott, who is Black, had recently moved to Oklahoma from Wisconsin. He told the news nonprofit Oklahoma Watch in 2022: “I came to Oklahoma unaware of how deep racism can go. I never experienced what my parents had experienced. I arrived here on July 2, 1987. By Nov. 5, 1987, I was in jail for rape, robbery, burglary, and a bomb threat, and all I could say was ‘I didn’t do it.’”

When Perry Lott was finally released in 2018, Pontotoc County’s then-district attorney, Paul Smith, wasn’t willing to call Lott “exonerated.” But by choosing to set Lott free, Smith was acknowledging that the DNA evidence in the case was persuasive. After all, Smith was agreeing to a “modification” in which 270 years was being shaved off of Lott’s 300-year sentence for rape.

So why do that if Smith still believed Lott was guilty as he told the media? Smith said simply that Lott had “already been punished a whole bunch.” The truth is there was more to the story. Smith conceded that going to court with Lott meant risking an adverse ruling from the judge based on the new DNA analysis. Not only that, Smith had no physical evidence on his side and was unable to find the victim who held the entire case together.

There was even more that prosecutor Smith was holding back from 2018 negotiations with Lott and the Innocence Project over a plea deal and release from prison. Smith neglected to disclose that one of the original detectives who investigated the case in 1987, Jeff Crosby of the Ada Police Department, had committed suicide two days before a key court hearing in the case to consider Lott’s claim of innocence.

This meant the prosecutor avoided troubling questions in court about Crosby’s record as an Ada law enforcer. It also meant that Crosby himself wouldn’t have to answer questions under oath. It turns out that during the early 2000s, Crosby was the target of an investigation by the FBI. Agents from the bureau dug into allegations of embezzlement, a gambling habit, drug use and dealing, and racketeering. In bureau records, they describe the existence of a “Jeff Crosby Organization.” The “organization” was “implicated by local law enforcement sources as being involved in the distribution of cocaine and methamphetamine.”

While working for the police, Crosby was also a blackjack dealer at a small casino near Ada. He was reportedly terminated from another casino over accusations of embezzlement. Agents wrote that he was involved in several disputes at the Ada Police Department. The “Crosby Organization,” they stated, “thrives in an atmosphere of fear and mistrust within the Ada Police Department and in the community of Ada at large.” Witnesses, including other police officers, feared retaliation and were afraid to provide information to the bureau. The FBI was never able to come up with enough information to press any charges, according to records. But their investigation still raised questions about Crosby’s integrity.

True gold tooth

After Donna Reed was sexually assaulted, she called the police, and a rape kit was collected from her at a hospital in Ada. Reed remembered that the assailant had a gold tooth in his mouth, according to a report from the Ada Police Department. The Innocence Project and Norwood.Law question whether this detail appeared in the police report only after Perry Lott had been identified as a suspect. Lott had a gold tooth at the time.

Hardly a day after the sexual assault, Ada police detectives Jeff Crosby and Mike Baskin were in the area investigating what happened. Waiting for a friend in his car nearby was Perry James Lott. Crosby and Baskin spotted Lott and decided to question him. From a distance, Lott shared only one distinction with the man described by the victim. Lott is Black. The detectives questioned him anyway and noticed that he had a gold tooth.

Lott said he had alibis. A friend verified that he was in the neighborhood to see her. Lott’s fiancée confirmed that they were in bed together the night before. According to a police report, Lott told the detectives that he didn’t know Donna Reed. But he agreed to give them pubic-hair samples, and he granted them permission to search his house and car.

He also agreed to go to the police station for further questioning. Two days later, he joined a lineup with several other Black men. Gold foil was applied to a tooth of each participant. Lott had the only true gold tooth, which made him stand out from the others. The victim asked Lott and another man in the lineup to speak. Then she identified Lott as the perpetrator. With no physical evidence in the case, Donna Reed’s word had to be enough. On Nov. 5, 1987, Lott was charged with burglary, robbery, and rape. He was convicted following a jury trial and sentenced in March of 1988 to 300 years of prison.

‘No deception’

By 2012, the national Innocence Project had decided Lott didn’t commit the crime and took up his case. It would be another six years before Lott was presented with the opportunity to walk out of prison. But then-District Attorney Paul Smith wasn’t willing to accept Lott as exonerated despite the DNA results excluding him from the rape kit in the case.

So Lott had a tough choice to make. He could continue to endure Oklahoma’s prison system while waiting to see if a court would vacate his conviction and exonerate him. Or he could accept a plea deal with Smith that meant he’d be known eternally as a convicted rapist. He would be required to attend a sex-offender treatment program and live on probation. He would also not be eligible to receive compensation for the decades he spent behind bars. Anxious to see freedom again, Lott accepted the plea. Prosecutor Smith told the media that he still believed Lott was guilty despite the deal setting him free.

But not only was there no evidence pointing to Lott as guilty, there was evidence pointing away from him. A fingernail was discovered on the victim’s bed. The Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation determined that it was not tied to Lott. He was also given a lie-detector test in 2019. Lott showed “no deception” when asked if he had sex with Donna Reed in November of 1987. And in addition to the rape kit, Lott was excluded from DNA found on the victim’s bedsheets.

“Perry had 30-plus years of his life taken from him,” Joseph Norwood said after Lott’s conviction was vacated. “He was wrongfully arrested and imprisoned as a very young man. He had an opportunity to get an education robbed from him. He had an opportunity to get employment and job experience – years of earning to provide for himself and his family – all robbed from him.”

Considering that the case was built entirely around a single eyewitness and no physical evidence, the victim was crucial to the prosecution. But Donna Reed has struggled in the past to prove that her identification of Perry Lott was unwavering. She revealed in a 2017 interview that nothing specific about Lott had stood out to her during the lineup. “There wasn’t nothing, you know, that screamed, hey, it’s me.” And: “I can’t think of anything that overly stands out that made me select him. … I can’t think of anything that makes him stand out.”

Her memory of specific details changed significantly at different times. Prosecutor Paul Smith cites as evidence against Lott the fact that Reed initially said her home was well-lit during the assault, meaning she ostensibly would have gotten a good look at her attacker. But in 2017, Reed said the contrary about the conditions of the attack: “My house was dark, you know … late at night.”

Blind lineups

There are also questions about the 1987 police lineup.

Witness misidentifications are a major contributing cause to wrongful convictions, and in particular, DNA exonerations. Yet juries are deeply influenced by eyewitnesses. Wrote Norwood.Law in one filing on Lott’s behalf: “Alarmingly, eyewitness identifications appear to be significantly more powerful than they are reliable. Put simply, Mr. Lott’s conviction was based on the cross-racial identification of a traumatized woman with a self-professed poor ability to provide physical descriptions who had survived a rape at gunpoint.”

Innumerable, peer-reviewed research studies have been conducted since Lott first went to prison that question the reliability of human memory and perception both in and out of the courtroom. Additional studies have challenged how lineups were conducted and whether detectives accidentally or intentionally altered their outcomes with suggestive remarks or visual cues.

The lineup procedures in Lott’s case would today not meet recommended best practices. For example, police did not use a so-called “blind administrator.” By not knowing who police believe is the suspect, a blind administrator helps prevent contamination of the process. Police also didn’t give the witness neutral instructions. To keep the witness from feeling rushed, they should be told that the investigation will not end simply because an identification wasn’t made on a given day. Police should additionally tell the witness that the suspect may or may not be in the lineup and that exonerating the innocent is as important as identifying the guilty.

Psychology researchers have made other important findings. When the perpetrator possesses a gun, it can draw the victim’s attention away from the perpetrator’s face. And contrary to what jurors tend to believe, surging stress levels can impair memory and lead to mistaken identifications. A final important phenomenon is well-established in the scientific literature. Human beings have more difficulty remembering the face of another person who isn’t the same race. Cross-racial misidentifications are common in DNA exoneration cases.” Wrote the Innocence Project in one of its filings:

“In light of the clear and irrefutable scientific evidence excluding Mr. Lott as the donor of the male biology on Ms. Reed’s vaginal swab, and in light of the fact that the only remaining evidence used to convict Mr. Lott – the eyewitness identification – is decidedly unstable by both the victim’s own account and the irrefutable social science, Mr. Lott’s conviction must be overturned.”