Norwood.Law client Corey Atchison of Tulsa spent 28 years in prison before a judge said he didn’t commit murder.

By G.W. Schulz

Investigators from the Tulsa Police Department wasted little time in 1990 before forming a theory that Norwood.Law client Corey Dion Atchison had committed murder. Once their sights were set, police and prosecutors embarked on a relentless campaign to take Atchison down even though witnesses had described someone else – a lifelong criminal – as the killer.

Atchison endured 28 grueling years in Oklahoma’s prison system before Norwood.Law helped get him freed in 2019. That year, a district judge in Tulsa finally reviewed the facts. She declared not only that Atchison’s trial was unfair but that he was “actually innocent” of shooting James Warren Lane to death on a darkened street in Tulsa’s Kendall-Whittier neighborhood.

When wrongfully convicted people are discovered to be innocent and set free after years or decades in prison, the public is often left wondering how it happened.

Don’t police need evidence of probable cause to make an arrest? Don’t prosecutors have a burden of proof to show that someone is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt? Why didn’t the jury stop it? The truth is that justice in America’s courtrooms is far different than how it appears on TV.

This chasm between public perception and reality is vast. In popular culture, police seem to always nab the right suspect. Evidence is obtained and analyzed with ease. Witnesses recall events with perfect clarity. Judges and juries rigorously review the facts and observe strict impartiality. Rarely are there nagging questions about alternate suspects, bogus leads from tipsters seeking rewards or fame, or deceitful informants hoping for leniency in their own cases.

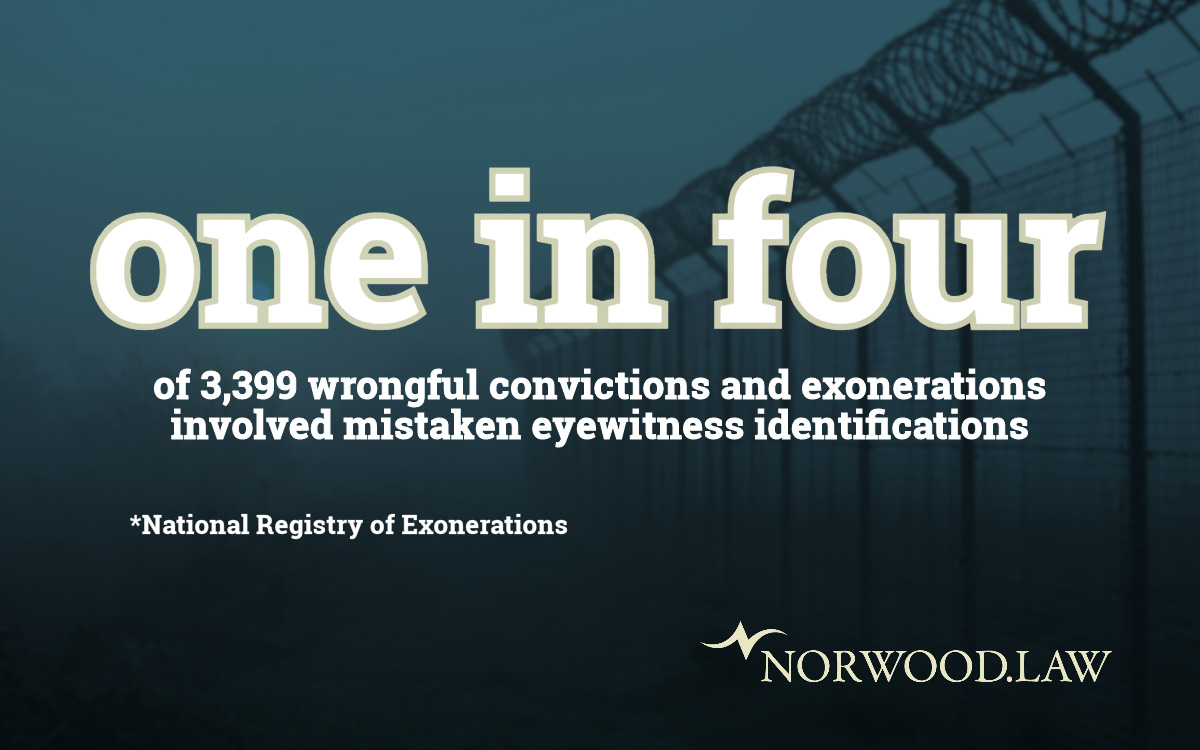

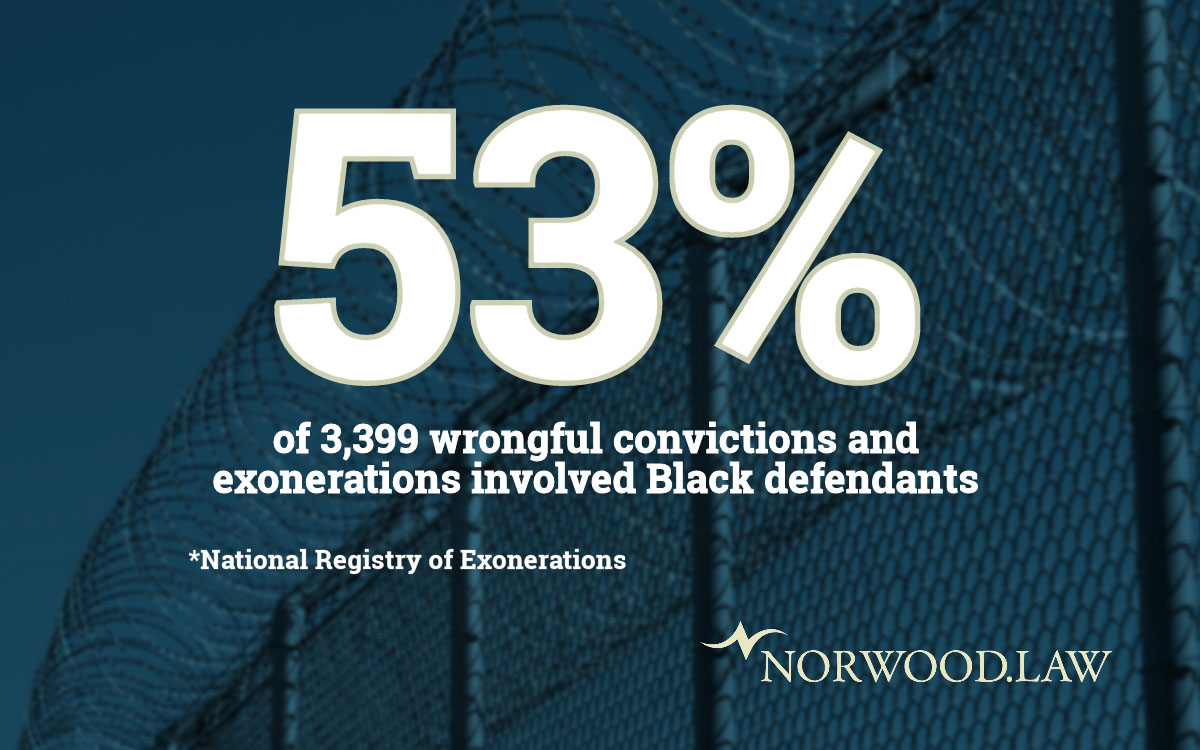

The truth is that everyone possesses psychological or cognitive biases that have sizable effects on how we form judgments. And these biases are partly to blame for the nearly 3,400 exonerations recorded by the National Registry of Exonerations since 1989 in which the wrong people were accused of crimes or there was serious doubt about their guilt. In one case after another, detectives and prosecutors have stolen years or decades away from people who were innocent or at least were not proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. This happened as true perpetrators got away without consequences.

Criminologists Kim Rossmo and Joycelyn Pollock of Texas State University wanted to find out why it happened so often when there seemed to be so many safeguards in place to prevent it. After closely studying 50 cases, they uncovered two major contributing factors: “tunnel vision” and “confirmation bias.” Their findings were published in a paper the same month that Atchison was set free.

Read on below for more about what Rossmo and Pollock discovered.

Are you mired in a legal dispute with the government, a business, or an individual? You’ll need relentless advocates to tell your side of the story. It’s not just criminal law we practice. If you find yourself caught in a personal injury, business, or family dispute, Norwood.Law will bring the same commitment and skill to your corner that we did to the case of Corey Atchison. When the day comes that you need our help, contact Norwood.Law for a consultation at 918-582-6464.

A vast spectrum

When “tunnel vision” occurs, police form a specific theory at the outset of an investigation and reject alternatives. Investigators develop an unshakable conviction that one suspect is guilty over another even if the evidence is pointing in a different direction. This leads to an unconscious filtering of information and is what happened to Corey Atchison. As more emotion, time, and money is sunk into a particular theory, authorities become evermore unwilling to consider alternate conclusions, Rossmo and Pollock write.

“Confirmation bias,” then, is a form of selective thinking that manifests as the investigation unfolds. Police narrowly seek out and interpret evidence to fit their theory. Not just investigators but all human beings experience confirmation bias and feel compelled to validate rather than refute a given hypothesis once it is formed. We selectively hunt for clues, interpret information in a way that supports our views, and wave off or ignore evidence that contradicts what we already believe.

Tunnel vision and confirmation bias affect criminal prosecutors, too. They may be facing a hotly contested election or have dreams of running for higher office. They want to be seen as a team player with police. If enough probable cause exists to make an arrest, then prosecutors simply assume the defendant is guilty. Write Rossmo and Pollock: “Prosecutors are invested in the belief that the defendant is guilty, because it is inherent in their professional duty to do so. … Once a decision to prosecute has been made, their training prepares them to consider contrary evidence only for the purpose of responding to and attacking such evidence.” Prosecutors become close to victims and families just like the police. And they’re trained to present cases in a way that ensures convictions:

“Media frenzy, ambition, ego, and office pressures for convictions can combine with cognitive bias and create the potential for a wrongful conviction. The idea of a ‘conviction psychology’ in a prosecutor’s office is the pervasive sense that all defendants are guilty, where racking up convictions is akin to ‘wins’ for a sports team. Only winning prosecutors will be successful in most prosecutors’ offices.”

In addition to detectives gravitating toward evidence that supports an existing theory, they might also turn away from evidence that disputes it. Take the case of Norwood.Law client Glynn Simmons who spent 48 years in Oklahoma’s prison system until being released when his murder conviction was vacated and case dismissed in 2023.

According to the available police reports, detectives made no apparent effort to check out the alibi Simmons gave them in the early stages of the investigation. In fact, 14 people ultimately testified or signed sworn affidavits that Simmons was in his hometown of Harvey, Louisiana, when a robbery and murder took place at an Edmond, Oklahoma, liquor store in 1974.

It was only later in 1975 while the investigation was underway that Simmons moved to Oklahoma City for a job. Authorities had no physical evidence to speak of in the case – no fingerprints, no DNA, no gun, and no surveillance footage. They relied instead on a single eyewitness who was shot in the head and by her own admission had glimpsed at the perpetrators for just a few seconds.

When witnesses recant

In the case of Corey Atchison, Tulsa police quickly targeted him after a young man was murdered in the summer of 1990. In fact, the police pursuit of Atchison started the night of the killing. Atchison and three friends turned the corner in Atchison’s car just as James Lane was shot to death in a suspected armed robbery and a group of males ran from the scene. Atchison, the oldest of the friends, yelled for someone to call 911.

The friends then waited for two hours with a gathered crowd before deciding to leave. Police thought they might have something to do with the shooting and searched them. They found nothing. Days later, a tipster who said she saw the shooting gave the name of a man to police. Two more tipsters gave descriptions that matched the man. This man would go on to twice serve 10 years in prison for armed robbery.

Yet authorities narrowed their focus to Atchison. By the time of the trial, two witnesses had “confessed” to police during interrogations that they saw Atchison carry out the shooting. In court, however, they both dramatically recanted their statements and said they were coerced by police. A third witness still maintained that Atchison did it.

But 26 years later, the third witness, too, recanted and said that he was also coerced. All three “witnesses” were teenagers at the time of the trial. With no physical evidence in the case – no fingerprints, no security footage, no gun – the case against Atchison collapsed. A district judge in Tulsa declared that not only was Atchison’s trial unfair, he was “actually innocent” of the crime.

Dangerously narrow-minded thinking by police in such cases can infect not just individuals but also groups in the form of “groupthink.” The Tulsa County prosecutor shared in the confirmation bias exhibited in Atchison’s case. According to Rossmo and Pollock:

“Critical thinking requires effort. An entrenched position, even an untenable one, can persist through psychological lethargy and organizational momentum. … Groupthink exacerbates tunnel vision and confirmation bias. … It occurs in highly cohesive groups under pressure to make important decisions. … Members selectively gather information, do not seek expert opinions, and fail to critically assess their ideas. … Groupthink can be disastrous in a major crime investigation as it distorts evidence evaluation.”

Tunnel vision typically appears first and then leads to confirmation bias. Tunnel vision as a concept is more commonly used in the legal community to describe accepting an available option as satisfactory while ignoring alternatives. But psychologists study confirmation bias within a vast spectrum of other known biases in our unconscious minds that affect how we form judgments about the world around us. They inform the way we think, but our conscious minds are largely unaware of them, which makes it difficult to stop or adjust them in real time. These biases can affect the perceptions of not just police but also prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges, juries, reporters, and the public.

For example, hiring managers can be swayed by the so-called “halo effect,” in which someone who attended a prestigious university or was the member of an elite college fraternity is favored for superficial reasons and may actually turn out to be an underperforming employee. “Affinity bias” can also impact hiring managers when they unconsciously favor interviewees who share similar experiences, interests, or backgrounds with the recruiter. Or, “status-quo bias” can prevent hiring managers from selecting bold, dynamic applicants in favor of those who are viewed as safe and consistent with past recruits.

Tunnel vision and confirmation bias are viewable in our daily lives. Imagine you want to travel to a luxury destination but are unsure you can afford it. In Google searches, you may tell yourself that you’re merely going where the facts take you. But in truth, you may be favoring links that promise such a trip is affordable and that you deserve a vacation. Journalists and news organizations undergo this filtering process, too, when deciding what stories to pursue, what research and statistics to spotlight, and what interview questions to ask. Only dates, times, names, and other such hard facts can truly be called objective.

Thinking errors

Rossmo and Pollock across their careers have extensively studied the effects of cognitive biases on the criminal justice system and published their findings in numerous papers. For this particular study, they looked at 50 wrongful convictions and investigative failures to determine how they happened and why confirmation bias and other “thinking errors” were so pervasive.

Three out of four cases the scholars scrutinized showed evidence of confirmation bias, according to their published findings. Nearly half the cases were affected by tunnel vision. Confirmation bias was the leading causal factor out of all of the cases. It was also a leading direct cause of failure in the cases. The scholars caution, however, that wrongful convictions are not caused by one factor alone. Several factors can be present and together lead to wrongful convictions.

Individual factors can be the cause or effect of another factor or both. In the cases Rossmo and Pollock reviewed, confirmation bias had the highest number of both cause-and-effect links among the determining factors. Causal factors of a wrongful conviction could be a media frenzy and public pressure following a murder, then the premature naming of a suspect, and then a biased search for and interpretation of evidence. Then investigators could ignore or mishandle critical evidence, interrogate the wrong people, or be overly trusting of informants.

In their published paper, Rossmo and Pollock looked at these three case studies:

- Jeffrey Deskovic, a teenager at the time, was convicted in 1991 of murdering a classmate. Investigators had “rushed to judgment” and quickly narrowed their attention to him. They still refused to believe he was innocent even after DNA test results excluded Deskovic. The real offender was exposed when further testing was eventually conducted. But that didn’t occur until Deskovic had spent 16 years in prison for the crime. “Rather than examine the evidence objectively, [authorities] shaped the evidence to fit their own theory without considering the possibility that they might have the wrong suspect.”

- Bruce Lisker also was a teenager when his mother was stabbed to death in 1983 at her Sherman Oaks, California, home. After the woman was found dead, police aimed their attention squarely at son Lisker, who was a drug addict and high-school dropout. A viable alternate suspect who later committed suicide wasn’t seriously considered by police. A jailhouse informant – in exchange for leniency in his own case – claimed that Bruce Lisker had confessed to the crime. Lisker was convicted of murder in late 1985. After a prolonged legal battle and 26 years locked up, Lisker was finally released in 2009. “A rush to judgment followed by tunnel vision led to confirmation bias. Exculpatory evidence was ignored. … Twenty-six years after Lisker’s arrest, a federal judge vacated his conviction ruling [that] he had been prosecuted with ‘false evidence.’”

- An Ohio woman and her six-year-old granddaughter were raped and severely beaten in 1998 by an intruder. The woman was killed but the girl survived. She later made a shaky identification of Clarence Elkins as the perpetrator, the woman victim’s son-in-law. He had no criminal record, and no physical evidence tied him to the scene. DNA eventually revealed another man to be the attacker – the neighbor’s common-law husband. But Elkins wrongly spent six years in prison for the crime. Convinced of Elkins’s guilt, police had neglected to do a DNA comparison and ignored blood at the scene. “This is a troubling example of the power of tunnel vision and confirmation bias. … Despite literally having the real killer next door, police ignored inconsistent physical evidence and exclusively focused on Elkins.”

Rush to judgment

To be sure, confirmation bias and tunnel vision don’t only affect police investigators. It’s visible in all of us. It’s apparent in the choices made by even highly trained people, such as doctors, scientists, business professionals, military leaders, and educators. Cognitive biases are not easily subdued through simple willpower. It takes more work to understand and account for them in one’s decision-making each day. According to Rossmo and Pollock:

“A rush to judgment is often the triggering problem. If investigators jump to a conclusion before all the evidence has been collected and analyzed, tunnel vision, and confirmation bias may result. Evidence discovered later will likely then suffer from a biased evaluation. Public fear, intense media interest, pressure from politicians, organizational stress, personal ego, or a strong desire to arrest a dangerous offender can all lead to premature judgment.”

There are other important contributing factors to wrongful convictions. The authors point to several:

- Misidentifications made by eyewitnesses

- Mishandled or misrepresented forensic evidence

- Questionable interrogation techniques and false confessions

- Lying by informants in exchange for leniency

- Misconduct by prosecutors and police

- Careless or overworked defense attorneys

Official misconduct can take the form of “noble-cause corruption.” This occurs when well-intended police and prosecutors conclude that it’s okay to break the law or violate the Constitution when they believe it benefits the public interest and a dangerous perpetrator will be locked up.

Another case study the researchers point to is the infamous wrongful conviction of Michael Morton in Texas. The murder of Morton’s wife and resulting media frenzy led law enforcers to follow their gut feelings to a suspect – her husband – and away from the evidence and facts of the case. That, in turn, led to confirmation bias in which detectives sought out and interpreted evidence to support their theories and ignored leads that presented a different reality.

The case bristles with confirmation bias. It was a high-profile murder in a “safe,” suburban community. The investigators were “inexperienced and incompetent,” Rossmo and Pollock write. Numerous evidentiary leads were ignored. Michael Morton was convicted in 1987 and sentenced to life before being exonerated in 2011:

“Investigators rushed to judgment regarding Morton’s guilt and prematurely shifted from an evidence-based to a suspect-based investigation. … The rush to judgment regarding Morton’s guilt led to confirmation bias resulting in a biased search for and interpretation of evidence. Innocuous events were distorted to support Morton’s guilt, while evidence pointing elsewhere was ignored.”

His case was handled so egregiously that his eventual exoneration after 25 years in prison led to a new Texas state law. The policy change was aimed at making it easier for defendants to obtain evidence from prosecutors that could prove their innocence. In Morton’s case, key evidence was withheld from him for years, including DNA from the scene. Another man was ultimately imprisoned for killing Morton’s wife. The true killer murdered another woman while Morton was in prison.

In many cases, to be sure, the guilt or innocence of a criminal defendant is not obvious, which is why we have the hallmark “beyond a reasonable doubt” legal standard. Its lineage dates to 18th century England when courts needed a rule for establishing guilt. Without it, jurors feared divine retribution should they convict someone who was innocent. In America, the prosecutor bears the burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt while the defendant enjoys the presumption of innocence. That’s the idea anyway.

Yet despite this legal standard, police, prosecutors, judges, and juries can still be utterly convinced of someone’s guilt only to learn years or decades later that DNA proved the crime was committed by someone else. Jurors experience their own form of confirmation bias in which they enter the courtroom possessing an inherent trust of law enforcement before they’ve heard any evidence at all. That influence is attributable to media effects and the fact that we’re culturally conditioned to give law enforcement the benefit of the doubt.

Rossmo and Pollock boast dozens more books, papers, and articles about policing on their list of achievements. Their paper here cites numerous similar studies that also examined the role of cognitive biases in criminal justice. Scholars in a 2013 paper, for example, wrote that tunnel vision was recognized throughout the available research on wrongful convictions as an important contributing variable. “It contributes to and facilitates system breakdown, because it dismantles the rigorous testing of evidence that makes the investigative and adversarial processes function effectively.”

A study from Michigan State University in 2009 found that when participants articulated a hypothesis early in a mock investigation, they pursued and interpreted evidence in a way that favored their theory. But participants who reflected on why the theory might be wrong showed less evidence of bias. Meanwhile, two University of Wisconsin law professors – one a co-founder of the Wisconsin Innocence Project – wrote in 2006 that tunnel vision is a cognitive distortion that impairs the ability of investigators to perceive and interpret the world accurately:

“In a sense, cognitive biases are a byproduct of our need to process efficiently the flood of sensory information coming from the outside world. … It is likely that most of the cognitive biases and heuristics that appear to be wired into us were adaptive to the conditions under which we evolved as a species.”

Failures resulting from these biases are missed opportunities to lock up the real perpetrators and prevent wrongful convictions. Rossmo and Pollock refer to wrongful convictions as “sentinel events” that betray deeper-rooted structural problems within the criminal justice system. As an example, they compare such investigative failures to aviation accidents where there are similarly numerous contributing factors. Unlike plane crashes, however, little effort is made following headline-grabbing exonerations to find out why they happened and why they happen so often.

The new legislation in Texas following Morton’s exoneration is uncommon. Even after colossal, obvious errors are made by authorities, the criminal justice system is often resistant to making major, system-wide changes. Wrongful convictions, the authors point out, tend to be blamed on a single “rogue detective” or “rabid prosecutor” and not institutional dysfunction.

In the wake of major aviation and hospital mishaps, on the other hand, investigations into what caused them are common. While it’s impossible to remove biases from one’s perception, it is possible to create procedures that can interfere with the damage they can unintentionally cause. Consider the safety checklists, after-action reports, and external-peer reviews that are often conducted prior to, during, and following surgical procedures, commercial flights, military operations, and research studies. From Rossmo and Pollock:

“Intuition, rush to judgment, tunnel vision, and groupthink all pose risks to objective and accurate evidence evaluation and analysis. … Biases, because they are implicit, are difficult to control. They function independently of one’s intelligence, and awareness of their dangers makes them no easier to avoid. … The development and testing of de-biasing training should be an important focus of future efforts to improve criminal investigations and reduce the frequency of wrongful convictions.”