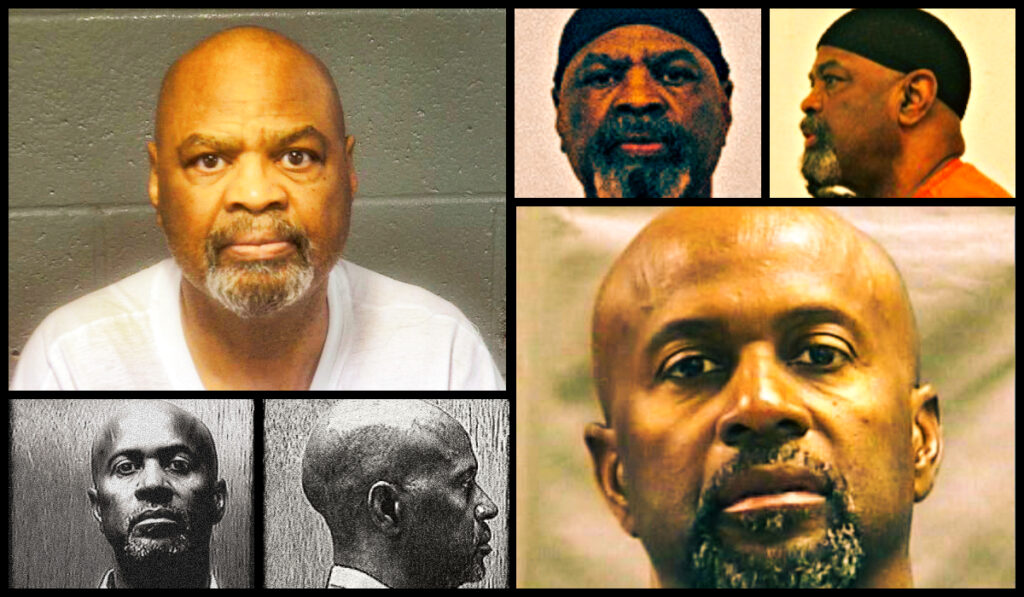

Glynn Simmons (top) and co-defendant Don Roberts

By G.W. Schulz

“Everybody realizes that eyewitness testimony is inherently unreliable.”

That’s what Tulsa County District Judge Sharon Holmes said in July of 2019 when she announced that Norwood.Law client Corey Dion Atchison was being exonerated of a Tulsa murder that took place in 1990. Atchison spent 28 years in prison for a crime that Judge Holmes finally, officially said Tulsa police and prosecutors got wrong.

In a typical TV portrayal of police investigations, forensic evidence conveniently appears to detectives with little effort. Footprints, tire-track marks, fingerprints, blood spatter, DNA, and surveillance footage all seem to fall easily into the hands of authorities. Then the evidence is analyzed at a glistening laboratory by an attractive scientist who deftly identifies a suspect.

But the truth is that investigators have commonly relied on flawed human eyewitnesses with no physical or forensic evidence at all to corroborate their claims. In doing so, they’ve sent the wrong people to prison for years, decades, life, or death row.

In announcing her decision to free our client, Judge Holmes pointed out that there was never any physical evidence presented against Corey Atchison in court. Instead, the Tulsa Police Department and the Tulsa County District Attorney’s Office relied entirely on eyewitnesses.

While on the witness stand, two of them recanted their statements to police that they saw Corey Atchison shoot and kill James Warren Lane in Tulsa’s Kendall-Whittier neighborhood east of downtown. By the time of the trial, the prosecuting Tulsa attorney, Tim Harris, had just one eyewitness left who was willing to say underoath that Atchison was the killer.

One eyewitness and no physical evidence turned out to be enough for a conviction that landed Corey Atchison in prison for nearly three decades. Continuing reading below to learn about the trouble with eyewitness testimony.

Are you caught up in a legal dispute with the government, a corporation, or an individual? You’ll need relentless advocates to tell your side of the story. It’s not just criminal law we practice. Norwood.Law will bring the same commitment and skill to your corner that we did to the case of Corey Atchison. When the time arrives that you need our help, contact Norwood.Law for a consultation at 918-582-6464.

‘Extreme care’

That lone, remaining eyewitness at Corey Atchison’s trial who held the case together also eventually recanted his testimony – 26 years later. The change of heart caused the state’s case to collapse. Judge Holmes concluded that all three witnesses in the case were teenagers at the time of the murder investigation and had been “coerced” by Tulsa authorities into calling Atchison a murderer:

“A common theme throughout this case was that those children were taken from school, taken to the detective division, and interrogated. At no time were parents advised that this was happening. … I actually had the transcripts from some of the interviews and, frankly, I have to tell you, I was appalled at how those interviews went.”

To argue her point that eyewitness testimony is inherently unreliable, Holmes cited what are known as the Oklahoma Uniform Jury Instructions. They specify, among other things, what judges are expected to tell jurors before trials commence about the fallibility of eyewitnesses.

According to the instructions:

“Eyewitness identifications are to be scrutinized with extreme care. Testimony as to identity is a statement of a belief by a witness. The possibility of human error or mistake and the probable likeness or similarity of objects and persons are circumstances that you must consider in weighing identification testimony.”

The instructions go on to list questions a juror should consider about witness identifications:

- How long did the witness see the alleged perpetrator?

- What was the distance between the subject and witness? What were the lighting conditions?

- Did the witness know the supposed perpetrator? Was the witness under stress?

- Did the witness remain convinced of the identification following cross-examination?

- Was the identification weakened by a prior failure to identify the person, such as during a lineup?

Over a period of decades, experts have conducted innumerable science-based studies that gradually exposed major weaknesses in eyewitness testimony. While representing another Norwood.Law client we believed was innocent, Glynn Ray Simmons, we enlisted the help of a PhD psychologist from Texas A&M University, Dr. Curt Carlson. Specifically, we asked Dr. Carlson to take a closer look at the case’s star eyewitness.

Like with Corey Atchison, police and prosecutors had relied almost entirely on a single eyewitness to prove that Glynn Simmons and a co-defendant had committed murder during a liquor-store robbery in 1974. A clerk was killed, while the star witness – a store customer – was shot in the head and survived. The witness admitted throughout the investigation and trial that she’d only been able to glimpse at the perpetrators for a few seconds before being shot.

Glynn Simmons has nonetheless spent a stunning 48 years in Oklahoma’s prison system for the crime. He was granted a new trial in 2023 by an Oklahoma City judge and will have a second chance to make his case to a jury. Simmons is out on bond. Meanwhile, the psychologist Dr. Carlson reviewed the facts of the case and relied almost entirely on a single eyewitness to prove and outlined numerous problems with the star witness.

Dr. Carlson observed, for example, that suspects should not appear in multiple lineups, because they can inadvertently become familiar to the victim or witness and lead to a false identification. Police should also use an independent administrator unaware of who police believe is the perpetrator. This would help prevent biased detectives from influencing the lineup’s outcome.

Next, the witness should be told that the perpetrator may or may not be present in the lineup. In the Simmons case, the star witness showed a low level of confidence in her choices. In fact, she initially identified someone during lineups who was neither Glynn Simmons nor his co-defendant, Don Roberts.

Research has shown that our memory of faces is greatly reduced after three weeks, which is the length of time between the robbery and the first police lineup. Faces of a different race than our own can also be more difficult to recall. The witness in the Simmons case is white, while Glynn Simmons and his co-defendant are black. The customer’s early descriptions of the perpetrators did not match Simmons. And the length of time the witness saw the perpetrators was too short to strongly enough “encode” what she saw into her memory.

Oklahoma in 2019 took steps to address faulty eyewitness testimony. Legislation passed that year by state lawmakers requires that lineups be conducted blindly, meaning the administrator does not know who the suspect is or cannot see who the witness sees. Witnesses must be told that the lead suspect may or may not be in the lineup. And eyewitnesses must state their level of certainty when an identification is made. What such laws don’t do, however, is prompt reviews of past convictions that relied extensively or entirely on questionable eyewitnesses.

Over the years that Simmons has spent in prison, his pleas for relief were rejected by state and federal courts as well as the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board. During the same month in 1999 that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit rejected one such appeal, federal justice officials issued a major set of recommendations crafted by experts on the use of eyewitness evidence by law enforcement:

“Even honest and well-meaning witnesses can make errors, such as identifying the wrong person or failing to identify the perpetrator of a crime. … During the past 20 years, research psychologists have produced a substantial body of findings regarding eyewitness evidence. These findings offer the legal system a valuable body of empirical knowledge.”

Below are some additional eye-opening case studies that illustrate just how easy it is for innocent people to wind up in prison or on death row following questionable eyewitness identifications.

Malcolm Scott and De’Marchoe Carpenter

Shockingly, Corey Atchison isn’t the only member of his family to be wrongfully convicted. His own brother spent 20 years in prison in an entirely separate case for a murder he didn’t commit. And it was the same judge in Tulsa County, Sharon Holmes, who released Malcolm Scott and his co-defendant, De’Marchoe Carpenter, in 2016 for many of the same reasons. The same detective from the Tulsa Police Department is even accused in separate lawsuits of coercing and pressuring witnesses into making false accusations.

Corey Atchison and his brother Malcolm Scott always had a tight bond. When a wrongful conviction struck the family again, it was 1995, just a few years after Atchison had been convicted of first-degree murder and sent to prison. In the second case, Scott and co-defendant Carpenter were accused by authorities of being involved in a drive-by shooting that took the life of a young woman named Karen Summers and injured two other people.

Like in the Atchison case, investigators seized on Scott and Carpenter as the suspects and refused to consider evidence pointing to someone else as the gunman. A car and gun found at the beginning of the investigation had implicated another man named Michael Wilson. That man confessed to the drive-by in 2014 just before he was executed for murder in an unrelated case. Scott and Carpenter, who were teenagers when they were first convicted, had already spent 18 years in prison by the time of the true killer’s confession.

Other details in the murder cases of brothers Atchison and Scott are eerily similar. There was never any forensic evidence tying Carpenter and Scott to the drive-by shooting, for example. Three witnesses in the case – including the true gunman, Wilson – recanted their statements to authorities implicating Carpenter and Scott.

Arvin McGee

The 20-year-old victim of a vicious kidnapping and rape stated with resounding conviction to authorities and in testimony that Arvin Carsell McGee was the man who had victimized her in 1987. But the availability of DNA analysis proved that despite her certainty, McGee was innocent. By the time McGee was exonerated and released in 2002, he’d been confined for 14 years.

Before McGee’s innocence was established, he was subjected to three different trials, two of which ended in mistrials when juries couldn’t agree on whether he was guilty. He was ultimately convicted and sentenced to over 350 years in prison. McGee had wound up in police lineups, because an officer believed he resembled a sketch of the offender.

The victim herself showed a lack of confidence during police lineups. She had at one point asked that the men in a live lineup be instructed to make verbal statements so she could listen for her attacker’s voice. The request was turned down. McGee was identified four months after the attack in a lineup of photographs. She had earlier identified someone else.

As Tulsa World columnist Ginnie Graham said about the case in 2019:

“It’s difficult to not believe a victim swearing with full, emotional detail that a specific person committed such an intimately violent act. It makes sense [that] a person being violated would have an ironclad memory. [But] that’s wrong, according to decades of science, social research, and exonerations.”

Michelle Murphy

The discovery made by police in 1994 was grisly. In the kitchen of Michelle Murphy’s townhouse were the bloody remains of her 15-week-old son who’d been stabbed to death. The body was almost completely decapitated. By the time prosecutors put Murphy on trial for the killing in 1995, they relied in part on the claims of a purported eyewitness from the neighborhood named William Lee.

The supposed witness told an investigator that he’d been walking the neighborhood that night, because he could not sleep. He heard quarreling from inside the townhouse as he walked by. Lee eventually testified that when he ventured out again into the neighborhood later in the night, he peeked through the kitchen blinds and allegedly saw Michelle Murphy with blood on her arms and the baby in a pool of blood on the floor.

Lee’s claims were pivotal to the prosecution’s accusation that Murphy had murdered her own baby. They also pointed to a supposed confession given by Murphy the night the baby was discovered. But police had recorded only 20 minutes of an eight-hour interrogation. Murphy was 17 years old and barefoot with shorts and a t-shirt at the time of the interrogation. She would ultimately retract the confession and assert her innocence saying that she’d been pressured by interrogators.

The truth was in the blood. A crime-lab analyst who testified at the trial concealed the fact that some of the blood discovered in the kitchen did not belong to the baby or Michelle Murphy. Not present at all was Murphy’s blood. But Murphy was locked up for some 20 years before proving her innocence. Not until 2014 did DNA testing of blood at the scene reveal the presence of an unknown male. The Tulsa County District Attorney’s Office chose to abandon Murphy’s conviction, and she was released that year.

William Lee, the supposed witness from the neighborhood, died of auto-erotic asphyxiation before Murphy’s trial got underway in 1995. The unknown male’s blood at the scene did not belong to Lee, however. Meanwhile, Tim Harris, the Tulsa assistant district attorney who criminally prosecuted Michelle Murphy, was also responsible for sending Norwood.Law client Corey Atchison to prison for a crime he didn’t commit. Prosecutor Harris went on to become the longest-serving elected district attorney in Tulsa County history.

Dennis Fritz and Ron Williamson

State and local police and the Pontotoc County District Attorney’s Office in Ada, Oklahoma, were under considerable strain during the 1980s to solve back-to-back killings of two young women two years apart in a quiet, country community where homicides were uncommon.

In the first case, Debra Sue Carter was found brutally murdered in her Ada apartment during the 1982 holiday season. Words had been written on Carter’s body in ketchup, and there was also evidence that she’d been sexually assaulted. A friend of Carter’s said that two men who “made her nervous” reportedly frequented the bar where Carter worked. Those individuals were Dennis Fritz and Ron Williamson.

From the outset, the available evidence against Fritz and Williamson was slim. It took five years for authorities to charge them with Carter’s murder. A witness in the form of a jailhouse snitch who was bunkmates with Dennis Fritz emerged with the claim that he heard Fritz confess to the killing. Another witness similarly alleged that she heard Ron Williamson make an admission. Most interesting of all, however, was a third witness by the name of Glen Gore who claimed to have heard Williamson harassing Debbie Carter at the bar where she worked on the night of the murder.

Fritz and Williamson were ultimately convicted of Carter’s killing in 1988. But after some 11 years behind bars, DNA analysis proved in 1999 that the two men were not responsible for the murder. It’s rare in such cases of exoneration for authorities to then pursue an alternative suspect. But the DNA turned out to be a match for Glen Gore who had previously testified to witnessing Williamson harass Carter the night she was killed. Gore was then convicted in 2006 and sentenced to life in prison for the murder of Debbie Carter.

The bestselling author John Grisham wrote a popular 2006 book about both high-profile Ada murders of the 1980s called “The Innocent Man.” It is the only work of nonfiction ever published by the prolific Grisham. The book went on to become a popular Netflix series of the same name that was launched in December of 2018. Read about the second Ada case below.

Karl Fontenot

Prosecutors relied on two things to convict Karl Fontenot of murder in 1985: Fontenot’s own supposed confession and statements from two eyewitnesses. The disappearance from Ada the previous year of Donna Denice Haraway has been covered exhaustively in local print and TV news stories, podcast episodes, a six-part Netflix series, and two books.

Fontenot and a co-defendant, Tommy Ward, were convicted and sentenced to death in 1985 for Haraway’s killing, even though her body had not been found. During initial interrogations, Fontenot and Ward confessed to murdering the young woman. But both men later recanted their statements. The two men’s cases were ultimately separated following their initial trial in 1985. With help from the former head of the Oklahoma Innocence Project, Fontenot in 2016 filed a writ of habeas corpus proclaiming his innocence.

During the some 35 years Fontenot spent locked up, the case against him unraveled. By 2019, U.S. District Judge James Payne had determined that Fontenot was innocent. Judge Payne found that Fontenot had been coerced by police investigators into confessing to the Haraway murder.

The judge also found that the two supposed eyewitnesses who identified Fontenot as being in the area where Haraway disappeared weren’t reliable witnesses after all. One of the witnesses recanted his statement that Fontenot was at the convenience store from which Haraway went missing. The second witness was pressured by police and the prosecution “to change her description of the men she saw” in the area of Haraway’s disappearance, according to Judge Payne.

Haraway’s remains were not discovered until several months after Fontenot and Ward were convicted. When her body was finally found, its condition did not match what the pair had described in their recanted confessions. Haraway’s body was discovered about 30 miles away from where Fontenot said she’d been left, for example. And while the men said in their confessions that Haraway was stabbed, the remains showed that she’d been shot.

The conviction of Tommy Ward was vacated in 2020 by a state judge, but it was then reinstated in 2022 and he was kept in prison. In the case of Karl Fontenot, he was let go after Judge Payne slammed police and prosecutors in his 190-page ruling:

“The Ada Police Department investigators turned a blind eye to many important pieces of evidence, relying instead on witness statements that fit their theory of the case while disregarding much stronger evidence of alternate suspects.”

Despite Judge Payne’s decision, Fontenot may still have to return to court in the future. A local district attorney in Comanche County, Oklahoma, two hours away from Ada filed a motion in the fall of 2022 seeking a new trial for Fontenot. But the Comanche County chief prosecutor has a steep hill to climb. As Judge Payne noted in his decision, “not one detail of Mr. Fontenot’s confession could ever be corroborated with any evidence in the case.”