By G.W. Schulz

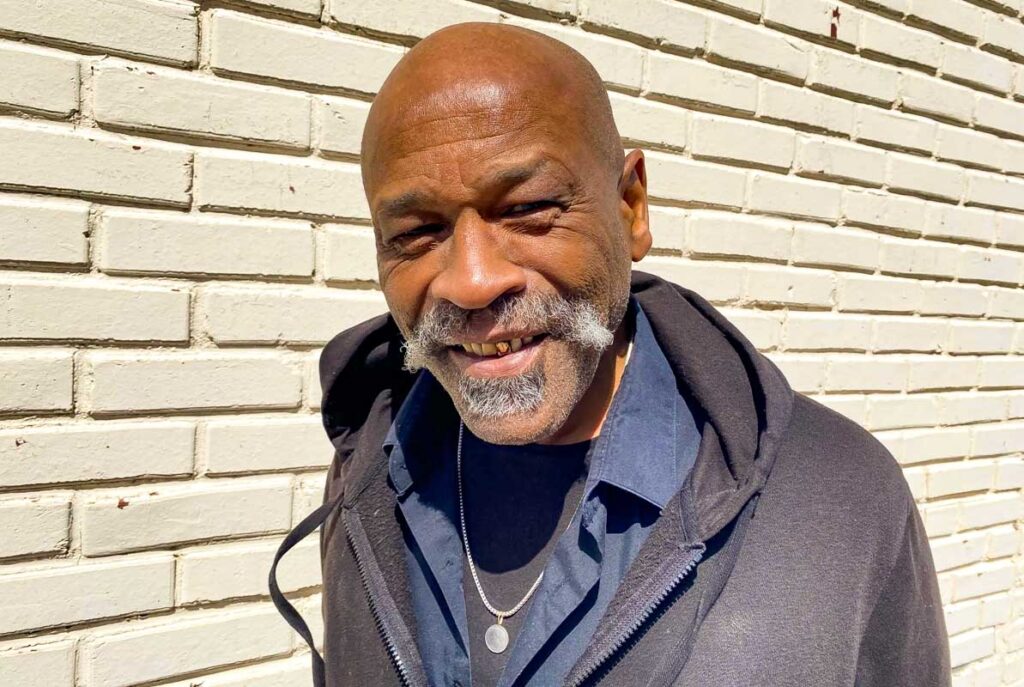

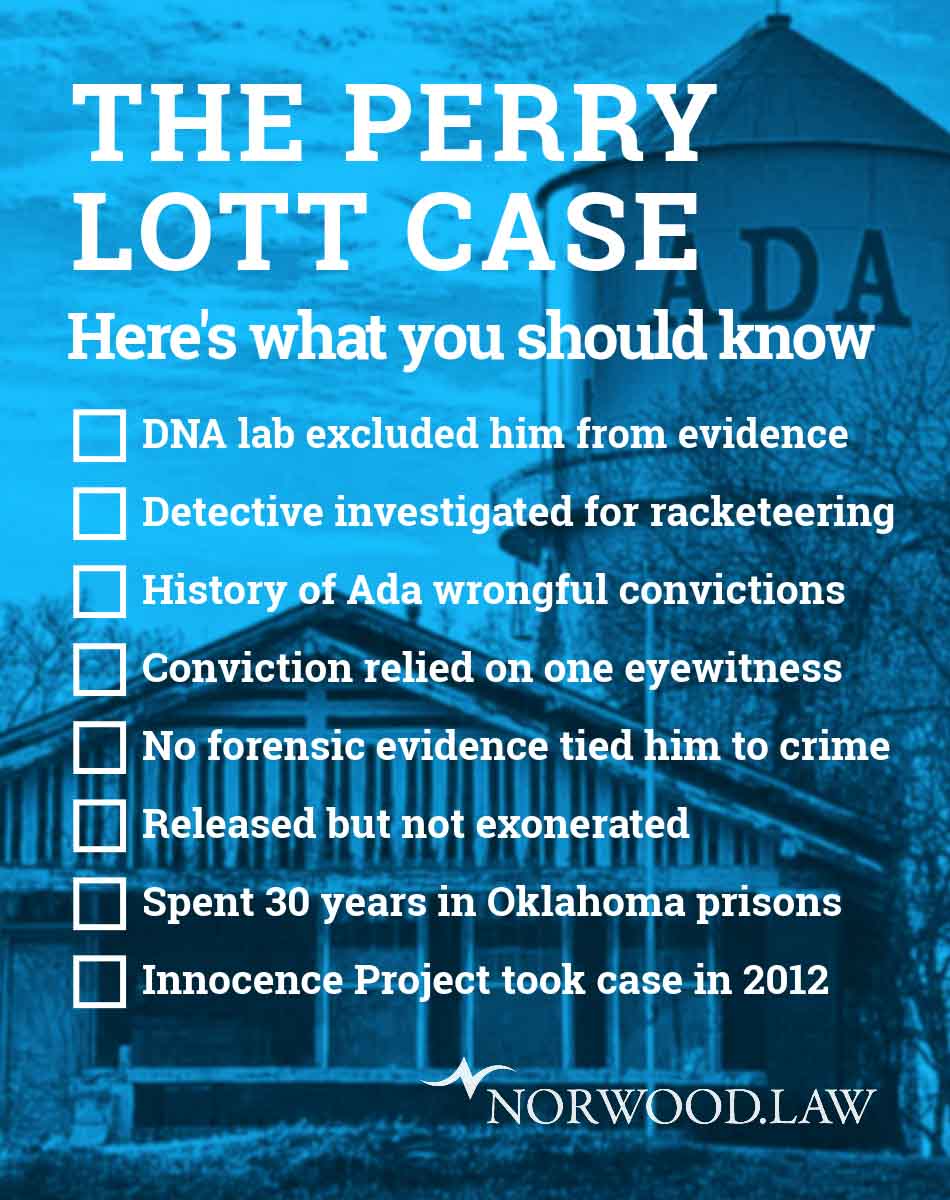

A state judge in southern Oklahoma will soon decide whether to formally throw out the conviction of a man who spent 30 years behind bars before DNA evidence excluded him from a rape victim’s vaginal swab. Perry James Lott, who is represented by Norwood.Law, was first set free from confinement in July of 2018 following a DNA analysis.

Only now is Pontotoc County District Judge Steven Kessinger in Ada, Oklahoma, weighing whether to go one step further and overturn Lott’s 1988 conviction for rape, burglary, and robbery. The deciding factor could be DNA technology that was unavailable when Lott first went to prison. Vacating Lott’s conviction would not mean he was “exonerated” or “innocent” of the crimes. But it would mean he was no longer convicted of them in the eyes of the law.

Yet another step would be necessary for Lott to meet the definition of “exonerated.” Erik Johnson, the district attorney for Pontotoc County, which is southeast of Oklahoma City, would have to decide whether to re-try the case in front of a fresh jury, offer a deal of some sort, or dismiss the case altogether. Any outcome would affect whether Lott met the criteria for entry into the National Registry of Exonerations, which has tracked over 3,350 wrongful convictions in the United States since 1989.

Led by the University of California Irvine, the registry says a person is exonerated when there’s “a dismissal of all charges related to the crime for which the person was originally convicted.” Further, the dismissal “must have occurred after evidence of innocence became available that was not presented at the trial at which the person was convicted.”

Criminal convictions can be vacated for any number of reasons. For example, it may happen where prosecutors prior to a trial failed to hand over evidence that pointed to a defendant’s innocence. Or it can result from key witnesses recanting their claims against a defendant. Or it can be due to defense attorneys giving their clients shoddy representation.

Driving Judge Kessinger’s decision to vacate Lott’s conviction would likely be more concrete: advancements in DNA testing. Specifically, Lott “was excluded as a source of the male DNA in this profile.” Those are the words of forensic scientist Meghan Clement of Bode Technology in Virginia. She conducted a review of biological evidence from the case’s rape kit and wrote up her findings in a 2017 affidavit. Lott has maintained his innocence since he was first arrested in 1987.

However, to gain his freedom back in 2018, Lott was forced to accept a compromise with prosecutors that meant he was still considered a criminal. At the time, former Pontotoc County District Attorney Paul Smith refused to recognize Lott as innocent despite what DNA evidence was showing. Norwood.Law’s efforts to fully exonerate Lott have continued in the years since.

Erik Johnson, the top prosecutor for Pontotoc County who took over in early 2023, may hold a different view of the case and be more agreeable to dismissal. If so, it would be a striking contrast to earlier Ada prosecutors, including the two who sent Lott to prison in 1988: Chris Ross and Bill Peterson.

During the same time period in the 1980s when Perry Lott was put on trial, Peterson and Ross helped vault the small, rural community of Ada into the national spotlight with their high-profile, zealous pursuit of four men in two separate murder cases involving young women victims. DNA cleared two of the men after 11 years in prison. A star witness in that case turned out to be the true killer. (Prosecutor Chris Ross played a limited role in the first case.) A third man in the second case was declared “actually innocent” and freed in 2019 after being incarcerated for 35 years. For the fourth man, a state judge dismissed his charges in 2020. But then he lost when the state appealed, and he has remained in prison.

Peterson and Ross are today retired but continued to defend their handling of the cases after they were tried in court. The cases have fueled innumerable news stories, podcast episodes, books, and other media. But arguably the best-known among them is “The Innocent Man,” a bestselling 2006 book by John Grisham, the prolific author of legal thrillers. The book remains Grisham’s only work of nonfiction and went on to become a popular, six-part Netflix series of the same name.

There’s even a sixth troubling Ada case dating back to 1982 that was handled by Bill Peterson’s office. A jury convicted Calvin Lee Scott of rape after just 30 minutes of weighing the evidence. Scott was sentenced to 20 years in prison. Hair samples supposedly linked Scott to the crime scene. Then DNA testing of a sperm sample showed that the evidence matched someone else. As a result, Scott was released from prison in 2003, but only after he’d been locked up for 20 years. Bill Peterson in the end was forced to concede that Scott had not committed the rape.

Continue reading below to learn more about Perry Lott’s efforts to prove his innocence.

If you’ve been accused of a crime, don’t wait to act. You’ll need Norwood.Law to tell your side of the story. And it’s not just criminal law we practice. If you find yourself ensnared in a family, business, or personal-injury dispute, Norwood.Law will bring the same commitment and skill to your corner that we have to the case of Perry Lott. When the time comes that you need our help, contact Norwood.Law for a consultation at 918-582-6464.

A difficult choice

Sexual assault is a matter of grave concern that occurs all too often in the United States and around the world. But no forensic evidence of any kind has ever connected Perry James Lott to the 1987 sexual assault of victim Donna Reed. With no physical evidence, the state’s case against Lott depended entirely on an eyewitness identification made by the victim in a police lineup. That was enough for Lott to be convicted and sent to prison in 1988. Not until March of 2014 did the rape kit become eligible for DNA testing. Those results showed that male genetic material contained in the kit did not belong to Lott.

In addition, Lott’s DNA was not found on any other piece of evidence recovered from the victim’s body and home. Criminalists from the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation, in fact, examined a fingernail found in the victim’s bed sheets and concluded that it did not belong to Lott. Then in 2019, he was subjected to a lie-detector test as a condition of his release. Such tests are not admissible as evidence in Oklahoma courtrooms. But Lott nonetheless showed “no deception” when asked if he had engaged in “any sexual activity with Donna Reed during November of 1987.”

Even though the DNA excluded Lott in 2014, it took another four agonizing years before he was finally presented with the chance to go home. In order to get out of prison, he had to make a difficult choice. Lott could continue to languish behind bars for months or years longer. During this time, a court would decide whether to vacate his conviction.

Or he could agree to a compromise with past-Pontotoc County District Attorney Paul Smith and be released in 2018. Under the terms of the agreement, Lott would not be exonerated of the crime or be viewed as innocent under the law. He would have to live on supervised probation and pay to attend a sex-offender treatment program. Not only that, Lott would have to wear the stain and stigma of being a convicted rapist. And he could not seek compensation for the 30 years he spent behind bars.

So Lott accepted the deal with prosecutor Smith in which Lott’s original sentence of 300 years was amended down to time-served. Karen Thompson, a former attorney from the national nonprofit Innocence Project, represented Lott for several years beginning in 2012. Thompson wrote in a 2018 letter that while she understood Lott’s desire to be free and his decision to accept the deal, she still wished the criminal justice system would do more in his case to right a wrong:

“While I am thrilled that Mr. Lott is now free and able to live – to some degree – a full life outside of the bounds of prison, this is simply not enough. Mr. Lott is an innocent man. He was failed by the justice system when it convicted him of a crime he did not commit. He was failed by the justice system when he had to accept an unfair plea simply to regain his freedom.”

A common problem

The story of Perry Lott resembles other cases around the state where defendants were wrongfully convicted or there was considerable doubt about their guilt. Two such cases involve Norwood.Law clients. Glynn Simmons endured 48 years in prison before being released in 2023 pending a new trial for a 1974 murder near Oklahoma City. Corey Atchison spent 28 years locked up before a Tulsa County judge in 2019 declared him “actually innocent” of a 1990 shooting death.

A familiar pattern binds many of these cases together. In the public’s imagination, police investigators responding to a crime enjoy an abundance of unmarred forensic evidence that savvy lab technicians effortlessly analyze into hard facts about the perpetrators. That evidence is then easily corroborated by unimpeachable witnesses who can summon memories of the perpetrator and crime scene with near-perfect clarity.

In reality, law enforcers often have no physical evidence at all linking the accused to the crimes. They rely instead on faulty or untrustworthy witnesses who are proven to be wrong or are simply lying. Or authorities hold up witnesses who later recant and say they were coerced. Defendants similarly make false confessions and later recant saying they, too, were coerced. For Glynn Simmons, Corey Atchison, and Perry Lott, prosecutors presented no forensic evidence in court and relied instead on a single eyewitness in each case.

It’s difficult to tell why Perry Lott became a target of police in the first place. Two Ada police officers spotted him in the area of the sexual assault shortly after it occurred and decided to question him. Only a gold tooth and the fact that he was black overlapped with what the victim allegedly described about her attacker.

Victim Donna Reed has recalled the details of what happened differently at different times. At Lott’s 1988 trial, Reed testified that her house was well-lit during the attack. Some thirty years later in a 2017 interview with a private investigator working for the Innocence Project, Reed said “my house was dark, you know … late at night.”

Reed admits she struggled to later identify her attacker. She said during the same 2017 interview that Lott’s voice helped her pick him out at the police lineup held in the days following the attack. But Reed also said that nothing in particular about Lott had stood out to her. “I can’t think of anything that overly stands out that made me select him. … I can’t think of anything that makes him stand out.” Also: “There wasn’t nothing, you know, that screamed, hey, it’s me.”

Fear and mistrust

Then in 2018 came a new, explosive revelation. A man named Jeff Crosby was one of the two original police detectives from Ada in 1987 who pursued Lott as a suspect in the assault. Some thirty years later, Crosby committed suicide. And he did so just two days before he was scheduled to testify at a hearing in the summer of 2018 about Lott’s possible innocence.

Crosby’s career, it turns out, had been punctured by suspicions of wrongdoing. Between 2002 and 2003, a federal probe by the FBI raised disturbing questions about Crosby’s ability to live by the very laws he was responsible for enforcing. Agents from the bureau looked into allegations of racketeering, drug distribution and use, a gambling habit, and embezzlement.

“Racketeering” refers to a criminal enterprise that schemes to profit through extortion, fraud, coercion, or other similar means. In records of the investigation, the FBI casually refers to the existence of a “Jeff Crosby Organization.” The records describe this organization as an “illegal drug distribution network” that had been “implicated by local law enforcement sources as being involved in the distribution of cocaine and methamphetamine.”

While captain of detectives at the Ada Police Department, Crosby was also a blackjack dealer at the small Rivermist Casino north of Ada. He was reportedly fired as security director from another casino over allegations of embezzlement, according to the FBI documents. Crosby also had been “involved in several internal disputes at the Ada Police Department.” From the bureau’s reports:

“The Crosby Organization thrives in an atmosphere of fear and mistrust within the Ada Police Department and in the community of Ada at large. … Witnesses and police officers are reluctant to provide information for fear of retaliation from Crosby and other officers at the police department. … Care must be used in gathering evidence in Ada, because the use of investigative techniques such as grand jury subpoenas will likely be leaked back to members of the organization through gossip.”

Although there was no shortage of rumors and allegations, FBI agents had difficulty substantiating them. The investigation of the “Jeff Crosby Organization” ran out of steam in August 2003, records show. No charges were filed.

When Lott’s evidentiary hearing arrived in 2018, then-Pontotoc County District Attorney Paul Smith neglected to tell Lott and his attorneys that Crosby had taken his own life and wouldn’t be available to testify. Prosecutor Smith thereby avoided an undesirable outcome at the hearing by negotiating the plea with Lott for time-served instead. Lott was given his freedom back after 30 years. But the DNA analysis wouldn’t exonerate him of the crime, and Lott would live on the outside of prison as a probationer and convicted rapist in the eyes of the law.

Not impressed

But if DNA testing had, in fact, excluded Lott from the rape kit, why did the government still consider him to be a sex offender? After arranging for the plea deal, prosecutor Smith in Ada said that he still believed the victim had identified the right perpetrator from a police lineup in 1987.

The DNA testing didn’t impress Smith. He pointed out that the attacker reportedly wore gloves and a condom and wouldn’t for certain have left a trail of DNA. But the forensic expert who interpreted the results from Bode Technology, Meghan Clement, said in her sworn affidavit that a condom wouldn’t necessarily have interfered with capturing the perpetrator’s DNA.

Smith has also claimed that the DNA evidence was contaminated. But extraordinary measures are taken at the lab where it was analyzed to ensure that no accidental contaminations occur, expert Clement stated in her affidavit. The DNA profile is searched against males with access to the testing facility, for example. It’s also compared to other cases being analyzed there at the same time. “Both these comparison searches yielded negative results.”

So if prosecutor Smith was still convinced of Lott’s guilt, then why did he agree to the release in 2018? According to statements Smith made to the media, Lott had “already been punished a whole bunch.” But Smith also confessed something else to the Oklahoman: His office had not been able to locate the victim in the case, Donna Reed.

And beyond the DNA, there were lingering questions about the police lineup in 1987.

Don’t scream

The rape and robbery of Donna Reed occurred past 1 a.m. on Nov. 3, 1987, a cool, fall night. Reed was unlocking the door of her home in Ada when someone approached her from behind with a gun. “Open the door and don’t scream, and I won’t hurt you,” the perpetrator said. She was shoved into her house where the woman was robbed of the cash in her purse.

Then Reed was instructed to remove her clothes, and she was pushed onto the bed, according to her testimony later in court. The man made sexual comments about a picture of Reed’s daughter. Then he put on a condom before raping Reed. Following the attack, Reed promptly contacted the police, and a rape kit of biological evidence was taken from her at an Ada-area hospital.

According to a report from the Ada Police Department, Reed recalled that her attacker had a gold tooth in the upper-left area of his mouth. But there are nagging questions as to whether this detail was added to the report only after Lott became a suspect, according to the Innocence Project. Lott had a gold tooth at the time.

Not long after the assault, two Ada police detectives, Mike Baskin and Jeff Crosby, were filming a video about what happened for Crime Stoppers near where it occurred. Crime Stoppers community initiatives still exist today and urge the public to report crime tips to police. The detectives decided Perry James Lott could be a possible suspect when they observed him in a car close to Donna Reed’s home.

They questioned Lott and noted that he had a gold tooth. Lott told them that he had alibis. He was in the area to see his girlfriend, which she verified. Lott also had a fiancee. He had been with her the night before, and then Lott left for work the next morning. She confirmed they were in bed together that night. According to a police report: “Perry said that he did not know Donna Reed, that she was not a girlfriend of his, [and that] he had not ever dated her.” Even so, Lott agreed to go to an Ada police station for additional questioning. Not only that, he gave police permission to search his car and house, and he turned over pubic-hair samples.

Two days later, Lott agreed to participate in a police lineup with five other black men. A tooth from each participant was affixed with gold foil to resemble the partial gold tooth reportedly described by the victim. All of the participants were asked to smile. Out of the group, only Lott had an actual, partial gold tooth, which made him stand out. The victim asked during the lineup that Lott and another man step forward and say, “Don’t scream. Open the door.” Then Reed identified Lott as her attacker. He was arrested on Nov. 5, 1987, and charged with robbery, rape, and burglary.

What we remember

Since there was no physical evidence linking Lott to the crime, Reed’s identification from the police lineup formed the heart of the case. But the Innocence Project pointed to several concerning factors about the identification in a 2017 court filing known as an application for post-conviction relief. Norwood.Law submitted a detailed supplemental to the court in August of 2023.

To begin with, misidentifications by witnesses and victims are typical in wrongful conviction cases. In recent decades, research psychologists have uncovered a universe of weaknesses in perception and human memory that raise questions about the reliability of eyewitness identifications. That’s the case no matter how confident a witness seems. Also, scientific research conducted since Lott was sent to prison has led to crucial findings about common mistakes made in police lineups that intentionally or unintentionally skew results. This is especially worrisome where there’s little or no strong, corroborating physical evidence.

Courts around the nation have gradually accepted this tidal shift in understanding about the natural flaws in eyewitness testimony. The reasons for misidentifications abound.

For example, people have a tougher time recalling the face of another person who is of a different race. It’s a “phenomenon well-established in the scientific research,” the Innocence Project wrote in its post-conviction filing. Perry Lott is black while Donna Reed is white. Second, jurors have a tendency to believe that traumatic episodes leave deep impressions on the memories of witnesses and victims. The opposite is true. Surging stress levels can negatively affect memory and lead to mistaken identifications. Additionally, the presence of a weapon – in this case, a gun pointed at Donna Reed – can draw the focus of the victim away from the perpetrator’s face.

Reed has admitted to not being good at recalling body types and not having a particularly strong memory of her attacker. Further problems can result from how a lineup is conducted by investigators. They might accidentally or even purposefully point victims or witnesses to a given suspect with suggestive comments or through lineup construction, for instance. The investigators in Reed’s case used lineup procedures that have since then been broadly criticized by experts.

Among other things, Ada police didn’t use a “blind administrator.” This person should not know who police believe is the suspect, which would help prevent contamination from visual cues or suggestive remarks. Police also didn’t use carefully crafted instructions for the witness that were consciously unbiased. Such directions, similar to those given to juries, help ensure witnesses are not unduly influenced by the perceptions and biases of the investigators or other factors. Examples of these instructions from the U.S. Justice Department:

- Inform the witness that it is just as important to clear the innocent as identify the guilty

- Tell the witness the suspect may not be in the lineup

- Ask the witness to state how certain he or she is of any identification

- Assure the witness the investigation will continue even if an identification is not made

The fact of the matter is that eyewitnesses have historically wielded significant influence over juries. According to research, that’s even the case when the witness was discredited by, for example, extremely poor eyesight. From another filing Norwood.Law wrote on Lott’s behalf:

“Eyewitness misidentification is the leading, contributing cause of DNA exonerations. In fact, studies indicate that misidentification is the leading cause of all wrongful convictions, not just DNA exonerations. … Alarmingly, eyewitness identifications appear to be significantly more powerful than they are reliable. Put simply, Mr. Lott’s conviction was based on the cross-racial identification of a traumatized woman with a self-professed poor ability to provide physical descriptions who had survived a rape at gunpoint.”

‘I didn’t do it’

To be sure, Perry James Lott admits that his life has not been without turbulence and poor choices. He was convicted in 1981 of committing robbery when he stole a woman’s purse. Lott was sentenced to a stint in county jail and probation. The following year in 1982, he landed in trouble again when he was convicted of robbing a convenience store. A court sentenced him to five years in prison, but he was released early on account of good behavior.

Both incidents occurred in Wisconsin where he grew up, and he pled guilty each time. No one was injured. Lott did not complete high school, but he also did not have any substance-abuse issues. He attributes the trouble from when he was younger to hanging out with the wrong crowd. It was later that he moved to Oklahoma from Wisconsin. Lott told the news nonprofit Oklahoma Watch in 2022:

“I went to jail for the first time for snatching a purse. What’s weird is that when I snatched the purse, I had a pretty good job. But I had these friends who were a pretty big influence, and I didn’t know I had a right to say no to them. … I came to Oklahoma unaware of how deep racism can go. I never experienced what my parents had experienced. I arrived here on July 2, 1987. By Nov. 5, 1987, I was in jail for rape, robbery, burglary, and a bomb threat, and all I could say was ‘I didn’t do it.’”