By G.W. Schulz

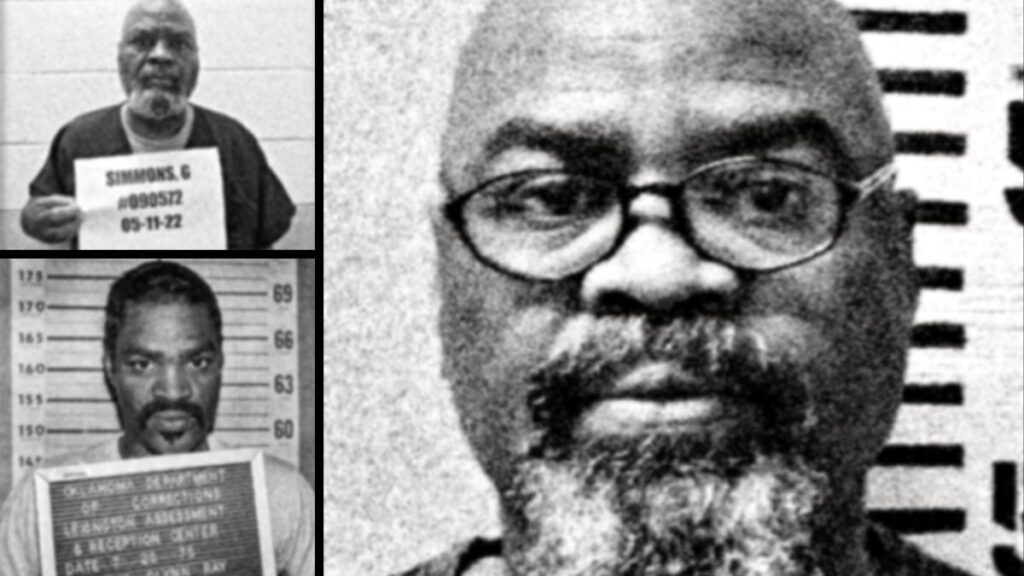

As the months, years, and decades slipped by without relief from a judge, Glynn Ray Simmons, a client of Norwood.Law based in Tulsa, edged closer to becoming the longest-serving wrongfully convicted man in recorded U.S. history. But that dubious distinction wouldn’t become a reality unless and until a judge or jury exonerated him of murder.

Now, with our help, Simmons is one step closer after an Oklahoma district judge chose to grant him a new trial.

Simmons has spent an astonishing 48 years behind bars for a 1974 liquor-store robbery and murder that took place in the suburban town of Edmond near Oklahoma City. With no physical evidence to go on, police and prosecutors built their case against Simmons largely on the questionable testimony of a single eyewitness who was a customer of the liquor store. She was shot but survived. By her own admission, the customer only glanced at Simmons and a co-defendant for a few seconds.

Oklahoma County District Judge Amy Palumbo has called for a new jury to reevaluate the case sometime in the near future. Informing her decision was an acknowledgment earlier this year by prosecutors at the Oklahoma County District Attorney’s Office that Simmons’s 1975 trial was conducted unfairly. They now admit that critical police records in the case were wrongly withheld from Simmons for 20 years. Those records contained damning information about suspect lineups from the 1975 police investigation and raised doubts about who the star witness in the case identified as the perpetrators.

A new trial gives Simmons a reason to be optimistic about the future. But we had hoped Judge Palumbo would absolve Simmons of guilt in the case entirely and obviate the need for a new trial by declaring him “actually innocent” of the crime due to “clear and convincing evidence.”

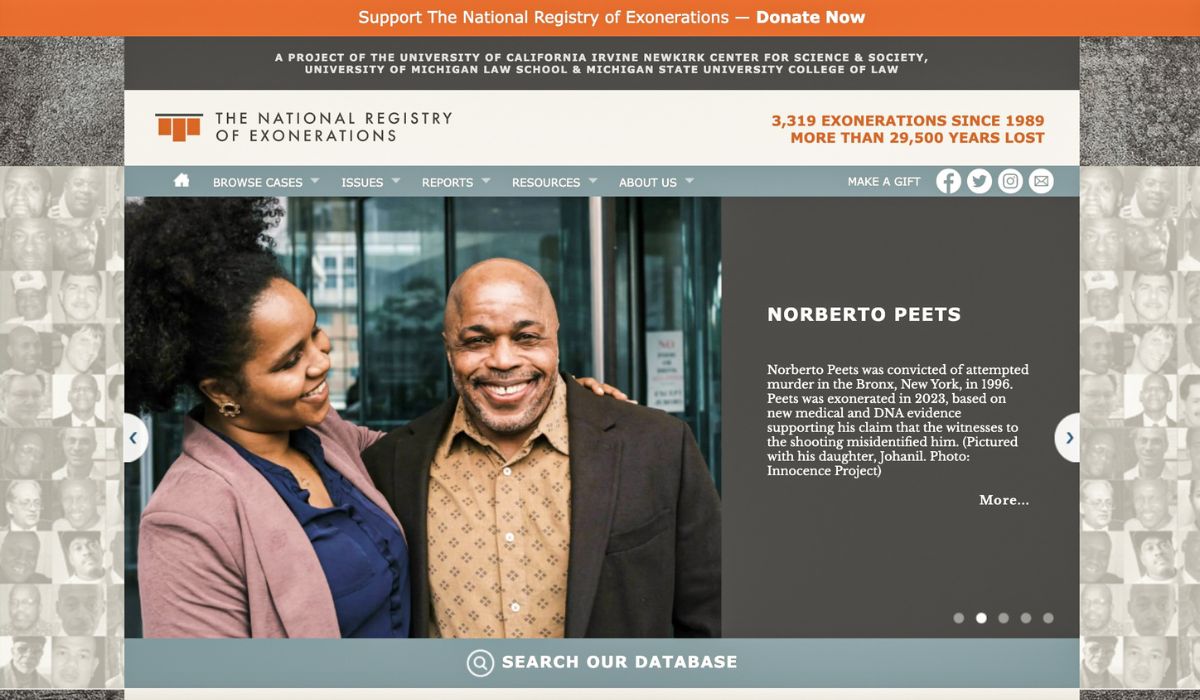

If she had taken that step, Simmons would not only have become eligible for the National Registry of Exonerations. At almost half-a-decade behind bars, Simmons could have been entered as the longest-serving exoneree in the database. Maintained by the University of Michigan and partner schools, the registry currently contains over 3,300 cases, and together they total nearly 30,000 years served for wrongful convictions.

Today, Simmons is 70 years old. He was just 22 when he entered prison. Simmons began corresponding with Norwood.Law after reading about how we helped free another man in 2019. After 28 years in that case, our client, Corey Atchison, was let go by Tulsa County District Judge Sharon Holmes. Judge Holmes ruled that Atchison was “actually innocent” in the case and that his treatment had been a “fundamental miscarriage of justice.”

After then learning about the Glynn Simmons case, Norwood.Law began to study the details contained in court records. We also examined the work of Oklahoma City TV reporter Ali Meyer and her news station, KFOR, who have covered Glynn’s story in-depth since 2003. You can find some of their work on Simmons here, here, and here. Continue reading below.

If you’re wrongfully accused of a crime by the government, you’ll need the most passionate advocates available to tell your side of the story. And it’s not just criminal law we practice. If you find yourself tied up in a personal injury, business, or family dispute, Norwood.Law will bring the same commitment and skill to your corner that we did to the case of Glynn Simmons. When the time arrives that you need our help, contact Norwood.Law for a free consultation at 918-582-6464.

Database of the wrongfully convicted

Without Glynn Simmons in the National Registry of Exonerations, Anthony Mazza is the current title-holder for the longest recorded sentence served by an exoneree. Mazza was released three years ago in Massachusetts after being imprisoned for 47 years. He’d been convicted in 1973 for tying up, robbing, and strangling to death a bank manager named Frank Armata. Numerous troubling questions surrounded a major witness in the case who was a roommate of Mazza’s and had initially been charged alongside him with the crime.

For Simmons here in Oklahoma, the wait to see how Judge Palumbo would rule in his case was tense. Since she stopped short of declaring Simmons innocent, he is not eligible to replace Mazza in the exonerations registry at this time. But the new jury could find him innocent. On the other hand, the new jury could vote Simmons guilty all over again.

Either way, a trial will take far longer than if Palumbo had simply decided to exonerate him on her own. Before handing down her decision, Judge Palumbo weighed testimony, briefs, and arguments from the case that were presented at an April 18, 2023, evidentiary hearing in Oklahoma City where we advocated for Simmons.

Simmons was initially sentenced in 1975 to death row along with a co-defendant, Don Roberts. But their sentences were later amended to life in prison. Roberts was eventually released on parole after serving 33 years. Glynn Simmons wasn’t so lucky and has been held for decades in the custody of the Oklahoma Department of Corrections.

Surprise support for Simmons

Amazingly, the original Oklahoma City prosecutor who sent Simmons and Roberts to death row in 1975 began having grave doubts over time about whether the right people were convicted. Former prosecutor Robert Mildfelt had even since written letters on behalf of Simmons in which he admitted that the case “had enough holes” that the jury could have just as easily acquitted him.

“Your case has troubled me these many years, because of the many questions unanswered by the evidence we had,” Mildfelt wrote in one such letter. “ … Quite candidly, it was one of the few cases I have been involved in that the verdict a week later could easily have been different.”

Dan Murdock, another prosecutor in the case, suggested similar misgivings to the media. He acknowledged to KFOR in 2014 that attitudes in the legal community toward eyewitnesses had shifted considerably. “We relied on eyewitness testimony… and we now know that’s not always best,” Murdock said.

Prosecutors aren’t the only ones who had doubts in the case.

A juror who voted to send Simmons to death row agreed decades later to appear on the reality TV show “Reasonable Doubt.” It devoted an episode to the Simmons case in 2021. The juror, Liz Thornton, expressed genuine surprise on camera to learn that the star witness had identified someone else in police lineups before Glynn Simmons and Don Roberts. Then Thornton appeared visibly stunned when told that prosecutor Robert Mildfelt had admitted to major reservations about his own case. In an extraordinary about-face, the juror said she no longer believed that Simmons was guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. “I do have doubts,” she told a co-host of the show.

Even the victim’s family has doubts. Carolyn Sue Rogers was the murder victim in the case who was shot and killed. Her sister, Janice Smith, has exchanged letters with Simmons and believes he should be released.

“He doesn’t deserve to be in prison. I do think he’s innocent,” Smith told “Reasonable Doubt.”

Robbery of a liquor store

The murder that landed Simmons in prison stems from a liquor-store robbery involving two men that took place on Dec. 30, 1974, in the town of Edmond near Oklahoma City. Clerk Carolyn Sue Rogers was shot in the head and killed. A customer was also shot in the head but survived.

Belinda Brown, the woman who lived, was just 18 at the time and planned to buy alcohol that night with a fake ID. She had only a few seconds to glimpse at the suspects before she was shot. Brown would nonetheless express with certainty in later testimony that the perpetrators were Glynn Simmons and Don Roberts.

A second clerk who was not harmed stood directly across from the perpetrators during the robbery and got a fuller look at them. Yet she never believed that her memory was reliable enough to make confident identifications of anyone, either in court or in police lineups.

Aside from these witnesses, there was no physical evidence at all in the case – no fingerprints, no gun, no DNA, no surveillance video. That meant 18-year-old Belinda Brown was the only meaningful, direct witness available to prosecutors, and she formed the heart of their case against Simmons and Roberts.

Problems with the witness

As part of our defense of Simmons, we asked a PhD psychologist, Dr. Curt Carlson of Texas A&M University, to conduct an expert analysis of this case. He identified several problems with the testimony of eyewitness Belinda Brown.

For example, by Brown’s own admission, she was only able to glance at the perpetrators for just a few seconds before being shot. That’s enough to miss key details about clothing, let alone faces, Dr. Carlson wrote in a report on the case.

The list goes on. There’s the traumatic brain injury Brown suffered by being shot. There’s the fact that two perpetrators instead of one can cause confusion and distraction for witnesses. There are the reports that Brown had poor eyesight. All of these factors and more could contribute to a false eyewitness identification, according to research studies cited by Dr. Carlson in his report. Further, Carlson wrote, human memory dampens quickly as it approaches the three-week mark following a given incident or experience.

Three weeks is how long it took for Belinda Brown to see her first lineup of possible suspects, during which she identified a man who was neither Glynn Simmons nor Don Roberts. The man Brown identified was let go after his alibi checked out.

Then in a new lineup two weeks later, Brown identified two new men who were not clearly named in the available police reports. Those records don’t plainly show that the two men were Simmons and Roberts. She identified the same two men again the following day, and again the available records don’t plainly show that it was Simmons and Roberts she picked.

Confusingly, among the records in the case is a separate, single-page document from the Oklahoma City Police Department that implies Brown pointed to Simmons and Roberts as the perpetrators all along. But the other police records that leave doubt about precisely who she identified were the ones withheld from Simmons and Roberts for 20 years.

At the 1975 trial, Brown would testify as if it had always been Simmons and Roberts that she singled out. At the time, Simmons’s defense attorney did not have the police documents showing that there were possibly others Brown had identified on two occasions from the lineups.

Officials admit trial was unfair

Just days before the recent April 18, 2023, evidentiary hearing before Judge Palumbo, the top prosecutor for Oklahoma County, Vicki Behenna, held a surprise press conference about the Simmons case. She conceded that Simmons was denied a fair trial when the key records about police lineups were kept from the defense in 1975.

But Behenna declined to say Simmons should be exonerated. Rather, she asked for the judge to start all over with a new trial. Behenna said at the press conference that she did not believe any new evidence “would show that Mr. Simmons is factually innocent of this murder.”

Judge Palumbo said at the April 18 hearing that the Simmons case had endured for so long, he was first charged with the crime before she was even born. Palumbo expressed irritation with prosecutors for having failed to acknowledge sooner that records were withheld from the defense. “It sure would have been nice for the state of Oklahoma to have confessed to this error before now,” she said.

Meanwhile, Simmons has long maintained that he wasn’t even in Oklahoma at the time of the robbery. Over a dozen alibi witnesses have testified or signed sworn statements saying that during the holidays in 1974, Simmons was actually in Harvey, Louisiana, where he grew up.

On Dec. 30, 1974, he was at two different pool halls. On New Year’s Eve, he visited with his son before again heading to two pool halls and a party. On New Year’s Day, he again visited with his son. At some point during this period, there was an informal football game that’s held every year as a local tradition. It was only later after the robbery that Simmons headed to Oklahoma City for job opportunities.

Now, no matter the outcome of the new trial, the criminal-justice system can’t give Simmons back the decades it has taken away. Even if the jury rules against the government, the system may never admit it was wrong. As we said in our extensive pleading from October of 2022 that called for Simmons to be released:

“By the time Glynn Simmons and Don Roberts came to the attention of authorities, the murder was five weeks old and the authorities had no leads. The public pressure to solve the case was enormous and undoubtedly weighed on law enforcement. It is logical that the law enforcement professionals may have felt this pressure and been so anxious to charge a suspect that they were desperate. Desperation leads to mistakes being made, and there were clearly mistakes made in this case.”